Devlog #1 — The Beginnings of a Game

We’ve now been working on No Space For Salad for a little over 2 months, and things have started to take shape.

In this post, I’d like to share a closer look at our development process. Maybe some of it will resonate with other small teams or solo developers working on their own projects.

It’s a method we’ve been using both for short projects (like game jams) and for longer, more ambitious ones.

The challenge for us with No Space For Salad is to develop the game within a limited timeframe (ideally 1 to 2 years for a first release) while continuing our work as independent creatives alongside it.

We’re lucky to work in the field of video games and interactive/immersive experiences, even if our own games don’t generate income (yet).

Like many indie developers, our long-term goal is to dedicate more and more time to our personal projects, and gradually reduce our reliance on client work.

We’re not working full-time on No Space For Salad. The amount of time we spend on it can vary wildly from week to week, depending on our other projects and commitments.

So as you read this devlog, keep in mind that progress happens at an uneven pace, but it does happen.

It all starts with an idea... and more importantly, with rest

I won’t spend too much time on this first phase. It’s the classic one: excitement, early ideas, a bit of chaos. That moment when everything seems possible and you throw a bunch of concepts at the wall to see what sticks. The goal is to uncover the essence of the project.

For No Space (that’s how we call it internally, No Space For Salad is a bit of a mouthful), everything began after a couch gaming session with Travellers Rest (great game, by the way).

We found ourselves chatting about what we liked or didn’t like about it. There are tons of restaurant sims out there, but this one really kept us playing for a long time.

At the time, we were still working on another (very ambitious) project, and had just wrapped up our jam game Lapinaut. Naturally, we started imagining what Lapinaut’s world might look like with a new gameplay loop, and how it could bring something fresh to the cooking genre.

Then we stopped talking about it.

For a while, a few months, the idea just kind of sat there. We’d bring it up occasionally, but nothing concrete was happening.

Here’s a personal tip: don’t rush headfirst into the first idea that gets you excited. Let it sit. Let it evolve. And if it still gives you butterflies after some time, then maybe it’s worth pursuing. But not before.

Of course, this kind of wait is only possible on long-term projects. In a jam setting, you can compress this phase into a much shorter window.

If your jam starts in the evening, take an hour or two to brainstorm freely, and pick one core idea. Then sleep on it, as much as you’re able to (sleep is crucial in jams!), and check how you feel about it in the morning.

Same if the jam starts earlier in the day: take a break, a meal, a walk, something to let the idea settle and shift without being totally focused on it.

I won’t go too deep into this part (many people already do it very well), but it’s helpful to jot down a few essentials at this point: a short concept description, a basic pitch, a list of pillars. And optionally: target audience, platforms, genre, playtime, etc. It just helps clarify your direction.

Setting a realistic and achievable goal

Alright, so you’ve settled on an idea.

Now it’s time to evaluate how feasible it is, based on your own skills, or those of your teammates.

At this stage, we try to list all the core mechanics or systems we want in the game. Not in full detail, but as exhaustively as possible.

Once we’ve got that list, we split it into two categories:

-

What we already know how to do (honestly, because we’ve done it before, not just because we think it’ll be easy)

-

What’s new or uncertain (novelty)

It’s really important not to overestimate yourself at this point. Staying modest doesn’t cost anything, and it can save a lot of trouble later. For beginners, especially, this is a useful step to avoid diving into projects that are far too ambitious.

Here’s a simplified version of what that looked like for No Space:

| Familiar systems | New or uncertain systems |

| Semi-isometric camera | Customization (restaurant layout, furniture) |

| 3D animated character | Local multiplayer split screen |

| TPS controller | Procedural generation (we’ve tried it before, but not at this level) |

| Inventory system | Restaurant management (cooking, service, etc.) |

| Oxygen & survival systems | |

| AI behaviors | |

| Progression systems (unlocks, purchases) | |

| Exploration harvesting (vacuum mechanic) | |

| Construction during exploration | |

| Multiplayer |

This list isn’t perfect, but it gives us a clear overview.

Then comes the key question: how does that breakdown look?

Ideally, you want something like 80% mastered systems and 20% new challenges. In the worst case, maybe 70/30. If it’s anything beyond that, you may want to reconsider things.

That doesn’t mean you should cut everything new, but maybe some features can be pushed aside or simplified. It’s also a great opportunity to get creative and come up with fun alternatives to features you can’t realistically implement (yet).

Now, for No Space, our balance wasn’t quite right… more like 60% known / 40% new. Which felt risky.

We looked at which “new” features we could safely remove without hurting the game’s core identity. And there was one that stood out: procedural planet generation.

In small-scale productions, hand-crafted levels have their pros and cons. But after thinking it through, switching to non-procedural level design became the obvious path.

Here’s what the new breakdown looked like:

| Familiar systems | New or uncertain systems |

| Semi-isometric camera | Customization (restaurant layout, furniture) |

| 3D animated character | Local multiplayer split screen |

| TPS controller | Restaurant management (cooking, service, etc.) |

| Inventory system | |

| Oxygen & survival systems | |

| AI behaviors | |

| Progression systems (unlocks, purchases) | |

| Exploration harvesting (vacuum mechanic) | |

| Construction during exploration | |

| Multiplayer | |

| Handcrafted level design |

That brought us to roughly 70% / 30%, which felt much more reasonable.

Breaking it down into milestones

Now it’s time to avoid spreading yourself too thin and focus on what really matters: building a playable prototype that shows off your game’s potential, and helps you address key technical and artistic challenges early on.

One approach that’s worked for us (in jams as well as larger projects) is to start with what we don’t know how to do yet.

By tackling unknowns early, you remove that lingering anxiety: “Will I actually be able to pull this off?”

It also helps you sort features by importance. If a mechanic you don’t master never shows up in your early prototypes… maybe it’s not that essential after all, and could be cut or replaced by something more familiar.

That’s exactly what happened to us with procedural generation.

To stay organized, we break the prototype down into several versions. Each with its own clear focus and goal.

Always build with a gameplay loop

Each version should include at least a basic gameplay loop (even a trimmed-down one).

Why? First, it gives you a better idea of whether your core idea actually works with minimal content.

Second, and just as important: it lets you start testing. And for that, having a loop is key, even a short one. You’ll quickly see how many times players go through it, and whether it feels good.

In No Space, our focus was on restaurant simulation and multiplayer interaction, that’s the heart of the game. Exploration, while important, came later.

Here’s how we split the work:

-

Prototype V1: 15–20 minutes of gameplay, focused on local split-screen and basic restaurant loop. Goal: serve customers in a full gameplay cycle.

-

Prototype V2: 30–45 minutes of gameplay, introducing exploration and the dual loop (exploration/cooking), along with basic customization.

-

Prototype V3: 45–60 minutes of gameplay, balancing both loops and adding early narrative elements.

After that, we’ll likely shift to preparing a demo or vertical slice, with more polished visuals and gameplay balancing.

Milestones need realistic timing

For each prototype version, we set a rough deadline. In our case, it’s about two months per version, which fits our hybrid schedule (between freelance work and dev time).

If you have more time available, you can obviously adjust your milestones accordingly.

You can also add shorter sprints (one or two weeks) with smaller goals in between each major milestone, whatever helps you stay motivated and focused.

When defining your goals for each version, try to be as detailed as possible. And once you’ve committed to a milestone, try not to jump ahead or start building features that don’t belong in it yet. Stay on track, it’s easier to start broad and refine later.

(And let’s be honest: who hasn’t spent hours polishing a totally optional mechanic before finishing their core gameplay loop?)

This mindset also applies to game jams. Define levels of complexity for your game, and build them step by step, without skipping ahead.

Starting with what you don’t know can be a good strategy: you’ll either validate the idea quickly or save yourself hours of stress down the line.

No Space – Prototype v01: Milestone Report

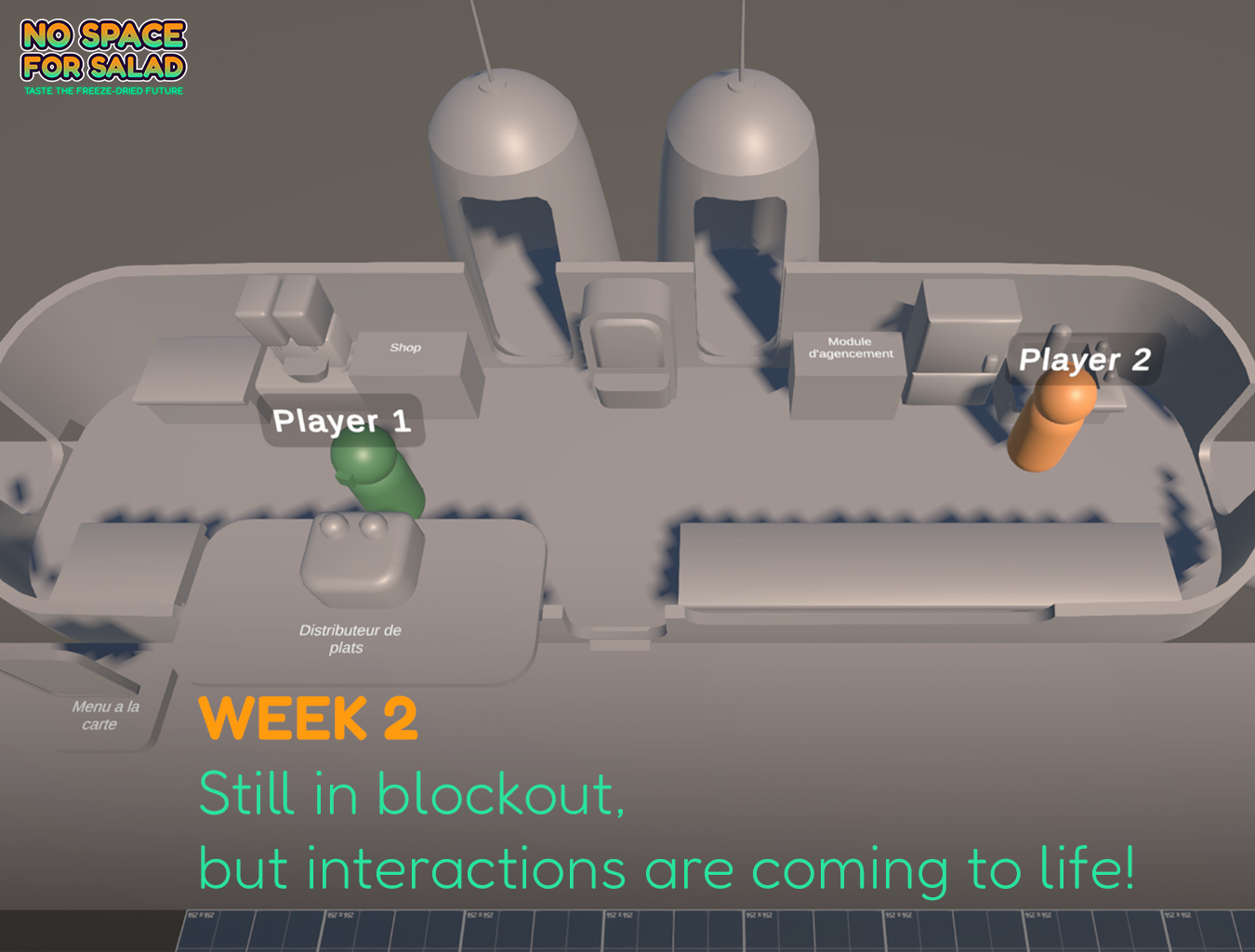

Last week, we reached our very first milestone.

We had set a soft deadline for early October, roughly two months after starting the project to complete a first playable prototype.

We began by tackling split screen, which was the feature we feared most and also one of the most central to our co-op gameplay.

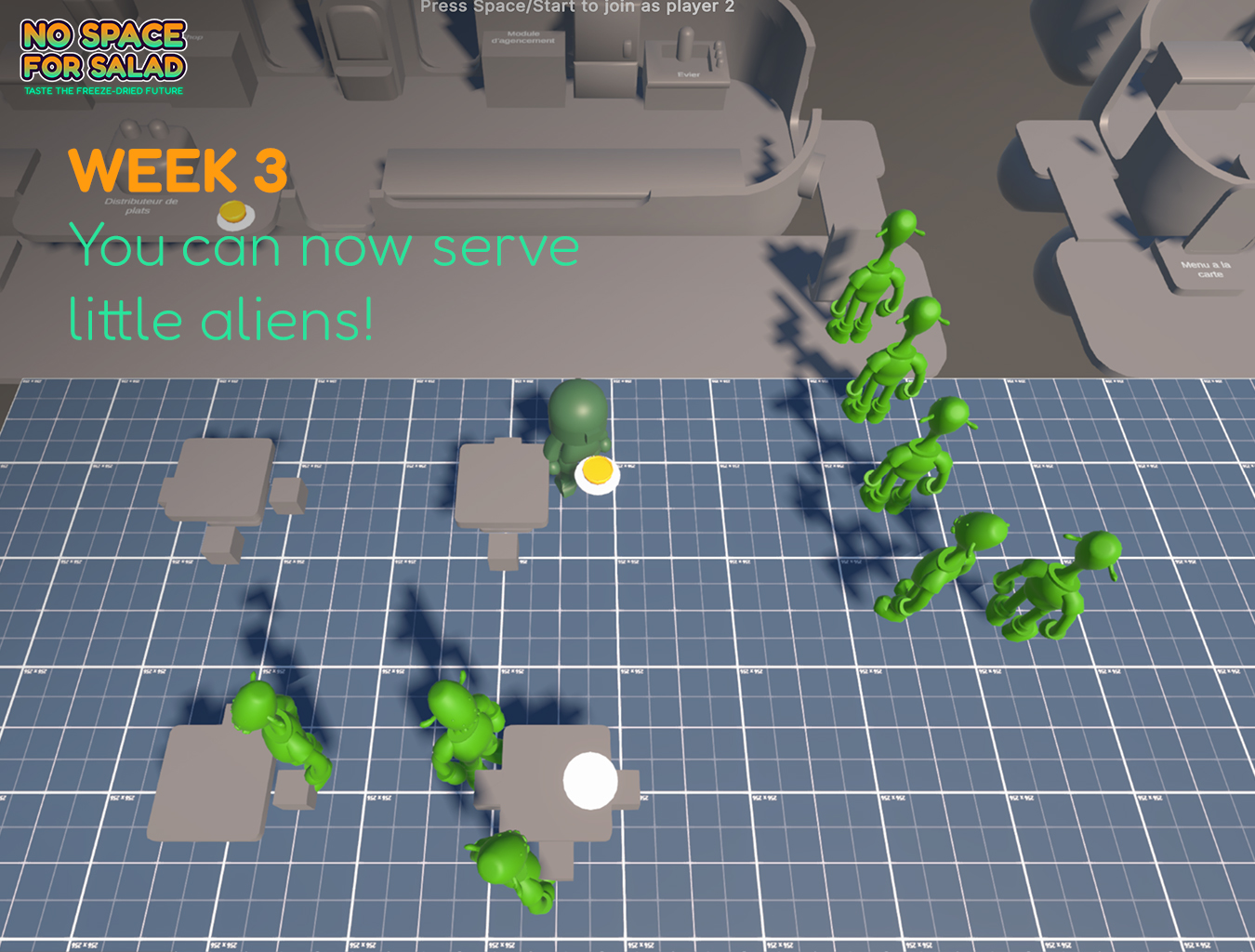

Then we moved on to the restaurant loop: customers arrive, place orders, you prepare their meals, they eat, pay, and leave.

We actually reached our gameplay loop goal a bit earlier than expected, so we decided to add a small slice of exploration using some elements from our jam game Lapinaut (reusing scripts) on a simple fixed map.

In the end, our testers played for around 45 minutes, while our goal was just 20 minutes which we’re really proud of.

Feedback and learnings

Overall, feedback has been very positive.

The cooking loop turned out to be quite addictive and kept players engaged for most of the session (about 70% of their playtime).

Split screen also worked smoothly and didn’t cause any issues.

We designed a fairly complex system to handle both sides of the game (kitchen/exploration), and we hope to dive deeper into that in a future devlog.

Exploration, on the other hand, felt too light in this version.

It didn’t grab players’ attention in the same way. Which makes sense, considering the development time spent on the kitchen loop compared to the exploration systems.

What’s next

Our next goal for Prototype v02 is to rebalance exploration, and make it just as engaging as the cooking loop. That’s our main focus, along with adding a touch of restaurant customization.

We’re keeping the same timeline of around two months, so you can expect to hear more about the next prototype version in early December.

Thanks a lot if you’ve read this far.

Hopefully this devlog has been useful, or at least interesting in some way.

If you have questions or feedback, feel free to leave a comment.

You can follow us on socials, or just drop by again for the next devlog.

No Space For Salad

A cozy, cooking sim where you run a food truck in space.

| Status | In development |

| Author | Tiidy Shell |

| Genre | Simulation |

| Tags | 3D, Colorful, Cooking, Co-op, Cozy, Cute, Exploration, Sci-fi, Singleplayer |

| Languages | English |

More posts

- Devlog #0 — What is No Space For Salad?Aug 06, 2025

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.